Record companies have spent more than a decade keening that free music was the subsidence in their basement and the dry rot in their rafters – so they are unlikely to be grandstanding about the fact that one of the biggest acts in the world is giving away his new album for nothing.

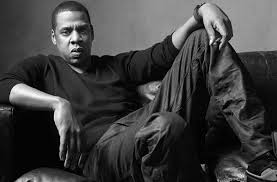

Well, not entirely for nothing – it comes with a catch. As part of a broader deal between Samsung and Roc Nation – estimated at $20m – a total of 1m copies of Jay-Z‘s new album, Magna Carta Holy Grail, were given away on Thursday at one minute past midnight (US eastern time), a full 72 hours before it officially goes on sale. The Korean mobile company has paid $5m so that the first million owners of Galaxy S III, Galaxy S4 and Galaxy Note II devices to claim the album though a free app from the Google Play store get a three-day headstart on the rest of Jay-Z‘s fans.

In the self-referential bubble of the music business, much has been made of the fact that, because it is free to consumers, those 1m “sales” will not count towards the charts in the US, the UK and elsewhere because of chart rules. But at $5 a copy, Jay-Z is almost certainly getting a far higher royalty rate than he would if those sales came from download stores or the dwindling number of record shops on the high street. The album is already a banker in an age when there are, in sales terms, few superstar certainties.

The scale of the deal did, however, force the RIAA (the US equivalent of the BPI) to make significant tweaks to its gold and platinum awards programme, meaning Jay-Z will get a nice shiny sales disc to put in his downstairs toilet straight away rather than having to wait 30 days (as per the old sales certification rules). This will now cover any digital album sales that previously had to wait a month to be qualified in order to allow for “returns” (unsold, but shipped, stock) – a throwback to the days when music was only available on physical formats. Yet within this all is a burning contradiction. The 1m album downloads are disqualified from the chart for being “free” to the consumer, but they count towards spraypainted discs in presentation frames because someone (in this case, Samsung) paid for them. Given the pre-hype and marketing spend, the album will almost certainly go to No 1 anyway on “normal” sales, so Jay-Z should win whichever way you slice it.

Beyond the cold, hard sales and revenue issues, this has revived, yet again, the debate about what it all means for investment in music and what the future of the album could be in an age of digital dislocation.

This is not quite a new form of blanket musical patronage – that is happening instead on Kickstarter and PledgeMusic where the public has the final say and where winning projects rise like rockets (Amanda Palmer, Ginger Wildheart) and stinkers sink (Björk’s Android app for Biophilia, a thousand terrible bands). This is about one megabrand (Jay-Z) linking with another megabrand to create that most 1980s of business terms – a “synergy”.

The benefit for Jay-Z, apart from a guaranteed $5m, is turbocharged promotion and profile raising. But the benefits for Samsung are potentially greater. For a company that spends an estimated $4bn a year on marketing, the $20m it handed over to Jay-Z and Roc Nation is chump change. To put that in content, global record sales last year generated $16.5bn – so Samsung throws a quarter of the gross value of the entire record business just at marketing every year.

Away from the boardroom cheers, it is not all wondrous news. For the fans, this is the diametric opposite of the Philips Red Book standard that, in the 1980s, dictated all CDs had to play on all CD players. Non-Samsung-owning fans are effectively being penalised for not having the right device and given the hard sell to upgrade, because this deal is really about atoning for the fact that Samsung’s own Music Hub music service has failed to capture the public’s imagination. This all says, arguably, more about Samsung trying to steal a march on the iPhone and iPad in the smartphone and tablet markets and using music to do that – just as Apple did with the iPod in 2001 and the iTunes store in 2003.

Handing out brand new albums for free is nothing new. Prince did it with the Planet Earth album on the front of the Mail on Sunday in 2007, and Radiohead did it with the tip jar release of In Rainbows later than same year (fans could choose to pay nothing to download it). The idea of an album-as-an-app is not new either (see Björk’s release of Biophilia for the iPad in 2011 and Gwilym Gold’s Tender Metal app in September last year). And brand partnerships long stopped being a novelty. The only thing that is really new here is the scale of the deal. It is all light years beyond Groove Armada being paid to be the “face” of Bacardi for a year.

It is proof of the continued lurch in the power balance that sees the music industry continue to dance to the tech industry’s tune, like chickens on fairground hotplates. It is also a premonition of the near future of the music business where 99% of the cash on the table will be mopped up by the top 1% of acts – the very ones who need the money the least.