At first, Elton John’s The Diving Board seems to suggest a statement of presence, nearly everything but the aging performer’s voice and piano kept to a bare minimum. 31 albums into his career, handfuls of mega-hit singles and platinum albums in the rearview, he’s sitting at the keys, opting for a simple background from which to stand out, rather than get swallowed up in elaborate arrangements. It’s almost inconsequential that Bernie Taupin wrote all of the lyrics, or that T-Bone Burnett ran the sessions; this is all Elton John, all the time. The problem with that Occam’s razor is that John’s voice isn’t quite as flexible as in years past, and that paired near-exclusively with a set number of piano keys makes for an occasionally flat, un-diverse record. But, John is a legend for a reason, capable of pushing the emotions and finding the hook even when the lines begin to blur.

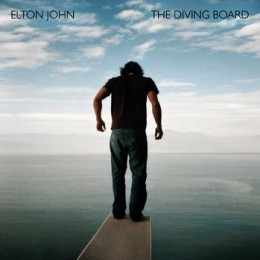

We’ve repeatedly had to face the quandary of a past-prime artist releasing a record over the past few years, and a 31st record here again begs the question of necessity. More Tumbleweed Connection than Goodbye Yellow Brick Road, the album finds John using some of the formulas from his earliest records to produce mature, classically-inflected songs. The spotlight focuses entirely on John on this album, as if he’s switched from a huge Broadway musical to a black-box one man show. While John has offered his unique take throughout his catalog and through the press, The Diving Board would (if you’ll pardon the too-direct linguistic connection) provide the perfect jumping-off point for extremely personal songs.

But, this isn’t a diary record. If these songs are at all connected to John’s personal life or view, the connections are oblique, often to the point of inscrutability. Flamboyant wit and raconteur Oscar Wilde is a subject here, but the dotted lines to the figure behind the mic aren’t connected. Else, the album is full of out and out characters, including auctioneers, war veterans, and tragic ex-pats. These are short stories set to song, rather than the pop songs he’s proven so capable of in the past, but they also lack the personal touch to enliven the subjects.

The inconsequential-seeming involvement of Taupin and Burnett, though, becomes increasingly important after each listen. Elton John shouldn’t be, in fact, alone in the spotlight. Taupin provided these characters, these narratives, to give John the perfect opportunity to emote. Burnett pulled the trigger on the minimal swashes of strings, the gospel choir that pipes up here and there. Both do their work, essentially, to get out of John’s way. The entrancing piano figure of “Oscar Wilde Gets Out” chimes into the subconscious for days, the jaunty “Mexican Vacation (Kids in the Candlelight)” offers a serious shot of adrenaline, and the trio of “Dream” instrumentals provide some of the album’s most captivating moments. His delivery of the somewhat trite lines of “Can’t Stay Alone Tonight”, thick and hearty, compensates perfectly. “You’re the diner in my rearview / A cup of coffee getting cold,” he croons, the line not saying nearly as much about the relationship as the way he sings it.

This 31st studio album won’t be anyone’s favorite Elton John record, or even necessarily a must-listen. The heavy reliance on the piano means that the Southern focus of “The Ballad of Blind Tom” and the Fleet Street narration of “Oscar Wilde Gets Out” don’t wind up sounding all that different. But, John’s vocals and technical playing raise nearly any song at least one rung up the ladder. Rather than recreate the past, the simplicity, the return to the sounds of his early albums, and the thoughtful story-telling reflect the place of a longtime legend keeping things in perspective. The union of John, Taupin, and Burnett stands out by being the best way for John to sound like he’s doing it entirely by himself. But, if he were to take the step further and use these tools to more clearly connect to the content of the songs, the emotional impact could be astounding.